Myanmar tea houses are more than cafés – they are the country’s living rooms, news hubs, and negotiation tables, all powered by strong Myanmar tea, sweet milk tea and endless plates of lahpet and snacks.

For Singapore-based travellers, expats and investors, understanding tea house culture is one of the fastest ways to understand everyday Myanmar life – and to read local neighbourhoods the way you might read an HDB void deck or kopitiam cluster back home.

This definitive Myanmar Tea House Culture Guide by Homejourney brings together cultural history, on‑the‑ground experience, practical travel tips, and strategic insights for anyone who may one day compare living in Yangon to Singapore’s city-fringe condos.

Table of Contents

- 1. Myanmar Tea House Culture Overview

- 2. History of Myanmar Tea and Lahpet

- 3. Anatomy of a Myanmar Tea House: What to Expect

- 4. Tea, Rituals and Everyday Life

- 5. Best Cities and Neighbourhoods for Tea House Hopping

- 6. Myanmar Tea, Milk Tea, Lahpet and Classic Snacks

- 7. Practical Travel & Safety Tips for Tea House Visits

- 8. Sample Tea House-Focused Itineraries (3 & 5 Days)

- 9. From Tea Houses to Property: Connecting Myanmar & Singapore

- 10. Reading Neighbourhoods Through Tea Houses (Investor Lens)

- 11. FAQ: Myanmar Tea House Culture, Safety and Singapore Links

1. Myanmar Tea House Culture Overview

1.1 Why Myanmar tea houses matter

In Myanmar, the tea house is a local hangout, informal office, news channel and dining room all in one. Locals start the morning with sweet milk tea, spend afternoons discussing politics and football, and close business deals over plates of lahpet (pickled tea leaf salad) and fried snacks.

For visitors used to Singapore’s kopitiam culture, Myanmar tea houses feel familiar yet distinctly different: more sprawling, more chaotic, and with tea playing an even deeper symbolic role in hospitality, social hierarchy and conflict resolution.

1.2 Best time to experience tea houses

Tea houses in Myanmar typically open around sunrise (5.30–6.30am) and stay busy until late morning, then again in the early evening.

Best times for atmosphere:

- 6.30–9.00am – office workers, students, and families; great for people‑watching

- 4.00–7.00pm – friends meeting after work; football on TV; louder and livelier

From a comfort and safety perspective – especially if you are travelling from Singapore with kids or elderly parents – aim for the cooler morning and early evening slots when streets are less congested and temperatures are lower.

1.3 Getting there from Singapore

From Singapore, Yangon has typically been the main gateway to Myanmar, with flight times of around 3 hours. Flight schedules and entry rules can change quickly; always verify current advisories with the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Singapore Tourism Board before booking.

For trip budgeting, many Singapore travellers treat a short Yangon or Mandalay tea‑house trip similarly to a long weekend in Bangkok, with slightly lower on‑ground costs for food and transport but more variation in accommodation standards.

1.4 Currency basics and tea house prices

Myanmar’s currency is the Kyat (MMK). Cash is still dominant, especially in local tea houses. ATMs are available in main cities but may be unreliable; bring some emergency USD or SGD in clean, newer notes to exchange at reputable money changers or banks.

Indicative tea house prices (city centre Yangon, pre‑tax and service; your actual costs may vary with inflation and exchange rates):

Use these as ballpark ranges only; currency volatility in Myanmar is high. Homejourney’s multi‑currency support can help you compare Kyat costs against Singapore property‑related expenses when you’re planning longer stays or considering cross‑border investment.

2. History of Myanmar Tea and Lahpet

2.1 Where Myanmar tea comes from

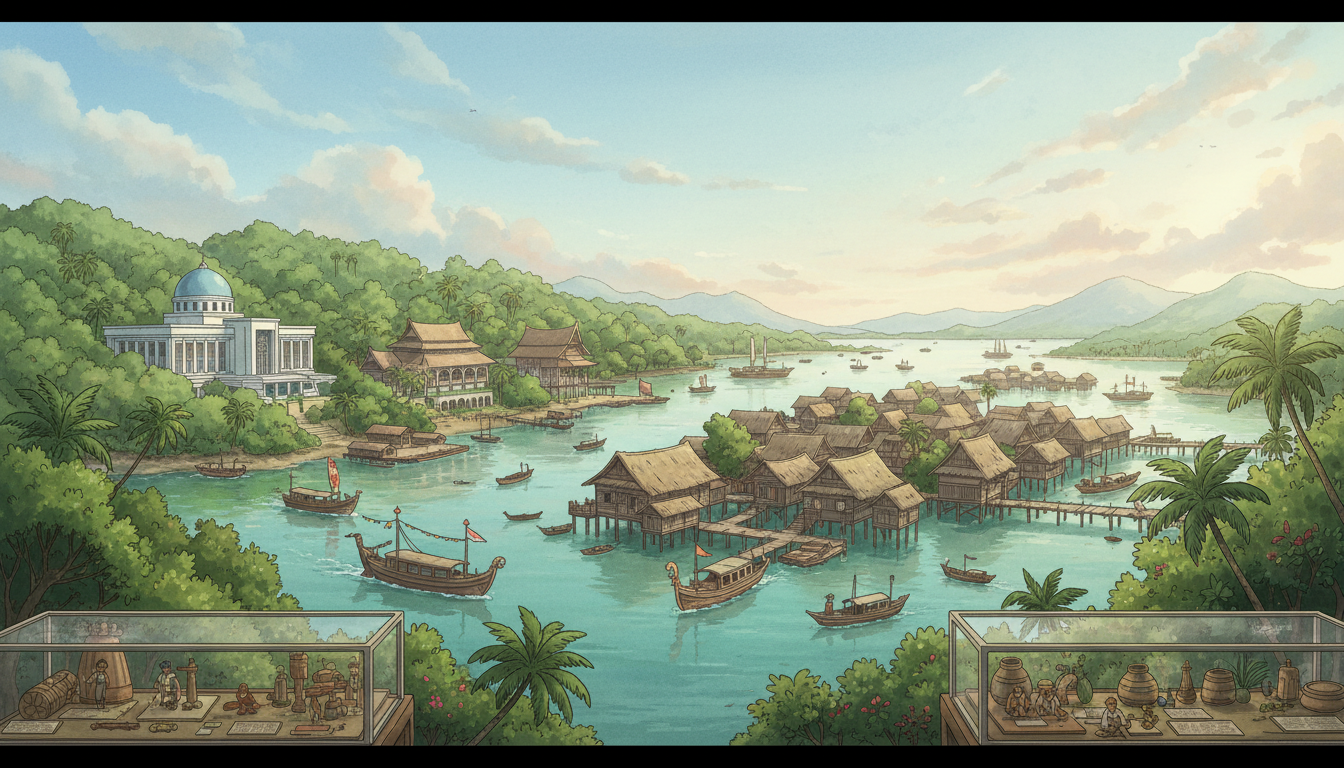

Myanmar’s tea story begins in the highlands of Shan State, where ethnic Palaung and Wa communities have cultivated tea for centuries. Historical and ethnographic research links the region’s tea culture to some of the earliest tea‑growing traditions in Southeast Asia, with tea grown both for drinking and as a key ritual offering.

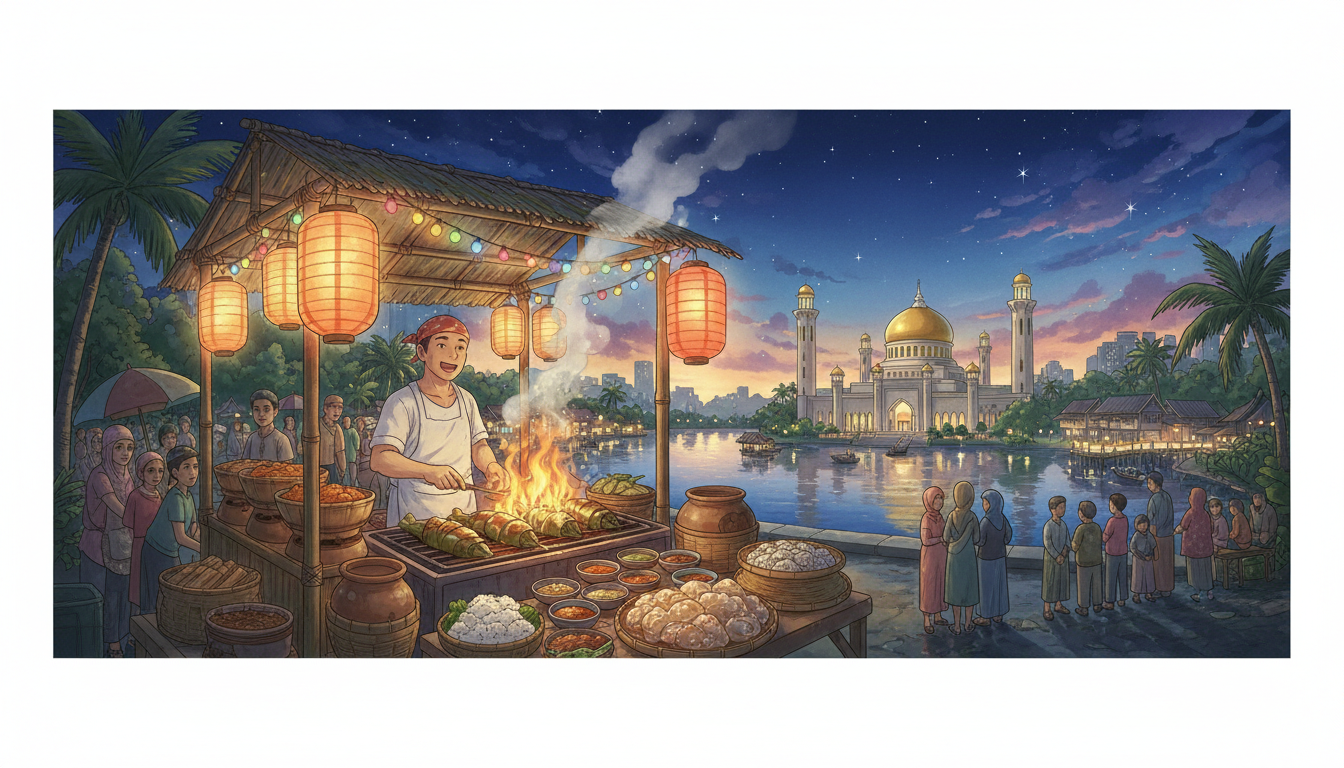

Unlike many countries where tea is only consumed as a drink, in Myanmar tea is also eaten as pickled leaves, especially in the iconic lahpet thoke – a combination of fermented tea leaves, crunchy nuts and seeds, and aromatics that is central to feasts, ceremonies and everyday snacks.

2.2 Lahpet as status, symbolism and social glue

In pre‑colonial Myanmar, lahpet held royal status. Historical records describe kings using tea sets as part of royal regalia, and lahpet being served at court events, religious offerings and important life ceremonies. Tea leaves and tea pots were even part of insignia granted to honour war heroes or high‑ranking officials.

Beyond the palace, lahpet became a way to seal agreements and resolve conflict. In some traditional divorce proceedings, both parties eating pickled tea together symbolised final acceptance of the court’s ruling – a powerful example of how deeply tea is woven into social and legal customs.

2.3 Tea houses as public living rooms

As urban centres like Yangon, Mandalay and Mawlamyine grew, tea houses emerged as semi‑public living rooms. In the early 20th century, photographs already show bustling tea shops where people gather to talk politics, read newspapers and share snacks.

Today, the same pattern continues: a tea house is where you hear rumours about a new condo launch in Yangon, compare school fees, debate football, or quietly negotiate rent with a local landlord. For Singapore investors used to gleaning neighbourhood sentiment from kopi tiam chatter beneath an HDB block, Myanmar tea houses play a similar, if even more central, role.

3. Anatomy of a Myanmar Tea House: What to Expect

3.1 Typical layout and atmosphere

A classic Myanmar tea house is noisy, bright and slightly chaotic – in a good way. Expect low plastic stools or wooden chairs, large shared tables, glass cups of milk tea balanced on metal trays, and a side counter stacked with snacks and ready‑made dishes.

Many tea houses spread onto the pavement with extra tables under big umbrellas or makeshift awnings. Fans might be the only cooling; air‑conditioned tea cafés exist in central Yangon and upper‑end malls, but the real cultural experience is in the open‑fronted, street‑level shops.

3.2 How ordering usually works

Compared with a Singapore café where you queue at a counter, Myanmar tea houses are usually table‑service.

Typical flow:

- You sit down; a staff member brings a pot of plain, unsweetened Myanmar tea (often free) and small cups.

- You order milk tea by sweetness level (more on this below) and any snacks or noodles from the menu or display counter.

- Snacks may arrive first, milk tea later – or vice versa. Refills of plain tea are usually free.

- When you are done, flag the staff; they count the plates and glasses, write the total on a scrap of paper, and you pay in cash.

Language tip: in more local spots, English may be limited. Pointing at dishes, using simple phrases and smiling goes a long way. Yangon and Mandalay’s more modern tea cafés often have bilingual menus.

3.3 The milk tea code: sweetness levels

In many Yangon tea houses, regulars customise Myanmar milk tea the way Singaporeans customise kopi or teh. While codes vary by shop, a common range includes:

If you prefer Singapore‑style teh si siew dai, say “less sweet” and, if needed, gesture by pinching your fingers to show “a bit” of sugar. In newer Yangon chains, some staff will understand “less sugar” or “no sugar”.

3.4 Types of tea houses you’ll see

Across major cities, you will typically encounter:

- Traditional street tea houses – Plastic stools, shared kettles of plain tea, open pans frying snacks. Best for atmosphere and local interaction.

- Modern tea cafés – Air‑conditioned, with pastry counters, Wi‑Fi and coffee options. Popular with students and young professionals.

- Hotel‑attached tea lounges – Safer food handling and better toilets, higher prices, less local vibe. Good if travelling with older parents or young kids.

For first‑time visitors from Singapore, a mix of at least one traditional tea house and one mid‑range modern café offers both authenticity and comfort.

4. Tea, Rituals and Everyday Life

4.1 Tea in religious and social ceremonies

Tea and lahpet are woven into ceremonies such as novitiation (shinbyu), weddings, ear‑boring ceremonies and religious donations. Serving lahpet thoke shows respect and generosity – similar to how Singapore families might serve yu sheng or kueh at festive gatherings.

Tea is also routinely offered to monks and at pagodas, reflecting generosity and devotion. Even in urban Yangon, it is common to see tea or bottled drinks left at roadside shrines and Buddhist images.

4.2 Tea houses as informal newsrooms

Before social media, tea houses were the original Twitter of Myanmar: people traded news, rumours and political opinions over cups of hot tea. That remains true today, especially in smaller towns where newspapers and online access may be limited.

For Singapore investors or expats doing on‑the‑ground research, sitting quietly in a neighbourhood tea house can offer a surprisingly accurate read of local sentiment, construction activity, and even rental trends – much like eavesdropping (politely) in a Toa Payoh kopi tiam.

4.3 Gender, age and tea houses

Traditional tea houses often skewed male, with older men spending long hours chatting, smoking and playing games. Today, especially in Yangon and Mandalay, women and young people are increasingly visible in tea shops and cafés, mirroring the broader urbanisation and education trends.

As a visitor, you will see schoolchildren with uniforms sharing a snack before tuition classes, office workers having quick lunches and multi‑generational families on weekends.

5. Best Cities and Neighbourhoods for Tea House Hopping

5.1 Yangon: Urban tea house capital

Yangon is Myanmar’s equivalent of Singapore in terms of density and variety of tea houses. You can find a tea shop on almost every block in the downtown grid.

Neighbourhoods to explore:

- Downtown (around Sule Pagoda, Pansodan, Anawrahta Road) – Dense, historic streets with old‑school tea houses and snack stalls.

- Kandawgyi and Bahan – More residential, with quieter tea spots tucked under apartment blocks, similar to Singapore’s mature estates.

- Yankin / Tamwe – Emerging middle‑class areas with modern tea cafés and bakeries, akin to Singapore’s city‑fringe districts.

As of recent years, typical taxi ride from the airport to downtown Yangon takes 45–60 minutes depending on traffic, somewhat comparable to a Changi–Jurong journey at peak hours.

5.2 Mandalay: Tea houses with a slower rhythm

Mandalay’s tea houses feel more spacious and slower‑paced than Yangon’s. Many open onto wide streets with less traffic, and you will see more long‑stay customers chatting for hours.

Areas around the palace moat and main markets are especially rich in tea shops, making them convenient bases if you enjoy walking between food spots and cultural sights.